Section 2 - Not So Simple Multiple Inheritance

10A.2.1 Not-So-Simple Multiple Inheritance

If each class, Base1, Base2, is derived normally, from SuperProtoBase (i.e. as we have done in the past) as in:

class Base1 : public SuperProtoBase

or

class Base2 : private SuperProtoBase

then the picture is more accurately described like this:

SuperProtoBase SuperProtoBase \ / \ / \ / \ / \ / Base1 Base2 \ / \ / \ / \ / \ / Derived

indicating that there are actually two copies of SuperProtoBase contained inside every Derived object, one belonging to Base1, and the other to Base2. Going back to our previous comments about parent classes that have members that are named the same, we must, from within the derived member functions or derived object, disambiguate using the scope resolution operator.

But what if we prefer to have only one copy of the SuperProtoBase members in each Derived object? We use the virtual derivation protocol:

class Base1 : virtual public SuperProtoBase

{

}

class Base2 : virtual private SuperProtoBase

{

}

Now, there is only one SuperProtoBase built in to every derived object, so no need to disambiguate.

The thing to remember is this: when deriving a class using the virtual keyword, nothing different happens at that level (i.e., in the class we are deriving). So the relationship between Base1 and SuperProtoBase does not change just because Base1 decided to derive itself virtually from SuperProtoBase. This is future planning, for the day when Base1 becomes a parent to some multiply derived class, a grandchild to SuperProtoBase.

Base1::Base1() : SuperProtoBase(3)

{

}

presumably storing 3 in one of SuperProtoBase's members, and Base2's constructor does this:

Base2::Base2() : SuperProtoBase(5)

{

}

presumably storing 5 in that same member, then would

Derived::Derived() : Base1(), Base2()

{

}

result in a 5 being passed into the SuperProtoBase constructor? Answer: No. This seems logical, but it just doesn't work that way. Instead, C++ requires that you call the virtual base class constructor directly from the most derived class if you want to pass parameters to it.

Derived::Derived() : Base1(), Base2(),

SuperProtoBase(12);

{

Also, it doesn't matter if SuperProtoBase(12) is placed to the left or right of Base1(), Base2(). It would be the only function call affecting SuperProtoBase members from these constructor calls in the function header.

Answer: No. That statement only applied to chaining the constructor calls, and the fact that the chain doesn't penetrate the virtual keyword. Inside the constructors you can manually set virtual base class members, and then, the rightmost function call will have the lasting effect on such members.

In the following examples I use the word struct in place of class. struct and class mean exactly the same thing, except that the default accessibility for struct is public, while in classes the default is private.

Compare these two programs. In the first, all derived classes rely on function chaining to set the base class data. Because of that, the "mid-level" classes, B and C, do not affect the final result of the base class data. Only the lowest level child, D, affects that value, and does so explicitly in the constructor chain call to the grandparent class A.

struct A

{

int x;

A(int n) { x = n; }

};

struct B : virtual public A

{

B(int n) : A(n) {}

};

struct C : virtual public A

{

C(int n) : A(n) { }

};

struct D: public B, public C

{

D(int n) : A(27), B(100), C(n){/* or "x = 27" here */}

void show() { cout << x << "!\n";}

};

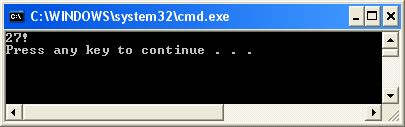

Produces:

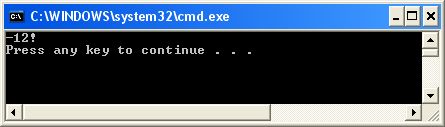

But in the next example, one of the "mid-level" classes, C, does not rely on chaining to set the base class data, but does it explicitly with a -12. Therefore, because the grandchild class constructor chains to C last (rightmost), that -12 will be the value that persists:

struct A

{

int x;

A(int n) { x = n; }

};

struct B : virtual public A

{

B(int n) : A(n) {}

};

struct C : virtual public A

{

C(int n) : A(n) { x = -12;}

};

struct D: public B, public C

{

D(int n) : A(27), B(100), C(n){/* like "x = -12" here. (need x = 27 to overpower C) */}

void show() { cout << x << "!\n";}

};

void main()

{

D d(25);

d.show();

}

As you can see, things can get pretty sticky in the land of multiple inheritance.